Now onward.

***

Monsters to the Left of Us...

After Part 14, which discussed the obsessive neoconservative campaign against science and modernity, can we take it that the Enlightenment is principally under attack from the "right"?

Far from it! Let's take another example of this all-out reactionary frenzy, this time from the political "left."

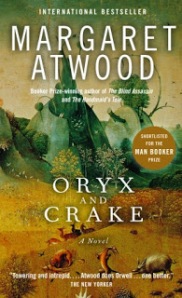

Michael Crichton's apparent polar opposite would seem to be Margaret Atwood, the doyen of feminist fiction and well-known for her attacks on the white-male-financier power structure, in both fiction and polemical nonfiction. Oryx and Crake, Atwood's latest novel, portrays yet another world devastated by human greed, incompetence, and brutish oppression, this time nearly denuded of human life by scientific innovations gone awry.

Michael Crichton's apparent polar opposite would seem to be Margaret Atwood, the doyen of feminist fiction and well-known for her attacks on the white-male-financier power structure, in both fiction and polemical nonfiction. Oryx and Crake, Atwood's latest novel, portrays yet another world devastated by human greed, incompetence, and brutish oppression, this time nearly denuded of human life by scientific innovations gone awry. Of course this is a familiar premise and one that I have used myself. Indeed, there is nothing wrong with some vivid extrapolative exaggeration in trying to make a point. The greatest 'self-preventing prophecies' have done it by showing how much we'd lose "if this goes on."

And yet, this motif can also become hackneyed, cliched, even a crutch. For example, nearly all feminist science fiction tales seem to begin with a scenario based on some (literally) manmade catastrophe. One can easily see why. The End of the World is such a bad thing - the very worst thing - that it offers a moral excuse for any author to pour opprobrium upon whole types who might be assigned blanket group-culpability. A neat trick, since you aren't really supposed to judge people in straw-man type-categories.

But that's what romantics inherently do, whether their particular ire is aimed left or right, at all commies or all capitalists or at all males. (See my article on Tolkien and the Modern Age) Romanticism is about one side being pure and good while the opposition is all-bad. And the attraction of this way of thinking is clear. Indignation feels good! It's lovely to disdain your opponents as-a class that is inherently immoral.

But even when your worldview officially promotes poilitically-correct hypertolerance? One way around this bind is to portray the enemy class (males, plutocrats, whatever) as all-powerful, and determined to bring about the end of the world.

(I expect grief from these paragraphs, so let me say very clearly that I consider myself to be a feminist and have written my own feminist utopia, Glory Season. Moreover, creating a cliched world holocaust and then assigning venal blame to conspiring corporate lords can seem less preposterous than Michael Crichton's recent attempt to call ecological activists the Great Illuminati! Here my criticism of the standard feminist fictional scenario is not aimed at the surface agenda of universal tolerance and opportunity - of which I deeply approve - but at a nasty undercurrent that many authors may not even be aware of.)

As part of this tradition, Oryx and Crake doesn't hold back. One of the book's key themes is the corrupting influence of commerce on science. When business interests dominate "you enter a skewed universe where science can no longer operate as science," Atwood says.

The book takes this to extremes. For example, biotech company HelthWyzer puts "hostile bioforms" into vitamin pills while at the same time marketing antidotes. "The best diseases, from a business point of view," the author writes with irony, "would be those that cause a lingering illness."

And it all goes to hell from there. Talk about a penalty for man's arrogance! The destruction of all art, all love, all hope. This is portrayed as the ultimate and likely outcome if we continue plunging forward with our insolent program of meddling with Nature's wisdom.

The crux: science cannot be trusted. Not while money or competition or self-interest are involved. (In other words, not while we are human.) Not anywhere as well as certain self-appointed artistic-elite guardians of Truth.

In effect, this is exactly the same lesson as that preached by Michael Crichton. Except replace "artistic" with "aristocratic." (The words even sound similar.)

Till now, I'd wager very few critics have even typed the names Michael Crichton and Margaret Atwood in the same article, let alone calling them allies and co belligerents in the same cause. And yet, having come this far in a lengthy essay, the reader can now see why I present them, side-by-side. True, they have probably never supported the same politicians, and never will. Their particular choice of villains will always be surficially different; so will their heroes and heroines. But those are superficialities and distractions.

Till now, I'd wager very few critics have even typed the names Michael Crichton and Margaret Atwood in the same article, let alone calling them allies and co belligerents in the same cause. And yet, having come this far in a lengthy essay, the reader can now see why I present them, side-by-side. True, they have probably never supported the same politicians, and never will. Their particular choice of villains will always be surficially different; so will their heroes and heroines. But those are superficialities and distractions. Indeed, this pair of authors show countless eerie parallels. Both claim relentlessly, and rather defensively, to be pro-science. Crichton avows a scientific education while Atwood often refers to her father and brother, biologists of some prominence. Both Crichton and Atwood mourn that modern science is relentlessly corrupted by corrupt interests that destroy its credibility. Even the unscrupulous conspiracies are remarkably similar, differing only in the cosmetic surfaces that distinguish left-wing authoritarian bogeymen from right-wing authoritarian bogeymen.

Both offer doomsday scenarios that arise almost entirely because of secrecy that stifles the natural corrective, error-prevention of open accountability in a free, democratic and scientific society.

And yet they never call secrecy the culprit, per se.

No, it is always hubris.

Dig down, and you will find that these authors, and a myriad others like them, tap the mythic current described by Joseph Campbell. A river of tradition, nostalgia and fear of the future that watered nearly all of the great literature in our tortured past, from Homer and Murusaki to Joyce. A despairing sense of loss. A belief in eternal verities and traditional values under threat. The rightful superiority of a wise or all-knowing class. A sense that the past knew better and that today's citizens cannot be trusted with bold new tools to "improve" the world. To improve their children and themselves.

Don't be distracted by minor differences. While lefty postmodernists express contempt for money-polluted, power-driven science in principle, Crichton and his neoconservative friends rail against what they perceive as a liberal-activist tilt on the part of the modern scientific community in practice, proclaiming that humanity's smartest and best trained minds -- the entire vast and amorphous marketplace of skilled scientific competitors -- have been polluted and discredited by outrageously unprofessional mysticism and consensual bias.

These two positions are seldom laid side-by-side. The common aim of antimodernists - both neoconservative and ultraliberal - is to discredit the process and credibility of science itself, a process that benefits from relentless criticism of specifics , but that is undermined by broadbrush general condemnations, hurled without supporting analysis from fanatical extremes of both left and right.

...on to Part 16... how it spreads outward from the arts...

.

40 comments:

"Indignation feels good!"

I remember seeing somehwere that there was a study that said the hormones and such released by indignation hit nerves in ways that made it addictive. I can't remember where I saw it though, and I haven't found it via Google yet.

Misdiagnosis of the problem seems to be the cause of a lot of problems in various things, especially politics. Like the hubris versus secrecy bit, where secrecy ends up with people overlooking something a five year old would have seen.

That's about all I can comment on, honestly, since I have to admit I hadn't even heard of Margaret Atwood before this.

Dr Brin,

A minor correction. Didn't you comment elsewhere that Glory Season was neither utopia nor dystopia? That was one reason why I consider that book to be so memorable - it was very even handed in the merits and demerits of that feminist society. I think you shouldn't lower yourself to calling it an utopia or dystopia just to take swipes at Magaret Atwood or Crichton. Instead, hold it up as a superior work, not becuase it refuses to take sides, but becuase it takes sides with awareness of pragmatics.

On the subject of postmodernism, if you didn't already know this, y'all owe it to yourselves to read about the Sokal affair. Sokal is a physicist at NYU who wrote a delightful parody of postmodern pastiche in "Social Text" and got the paper accepted(!) as a genuine article. The resulting fury from the postmodernists about being had was a thing to behold. Last time I checked, they were saying that while Sokal intended it to be a parody, it really wasn't and that genuine stuff snuck in.

After reading this, head on to The Postmodernism Generator and read a randomly generated postmodernism article. ROFL.

I'm not sure how well postmodernists fit into this dichotomy.

It seems that postmodernists are both anti-modernist AND anti-romanticist. Through relativism they reject the "eternal verities". Their agendas usually seem to be very socially progressive, indicating an understanding that the world of our children can be better than the world of our parents. At the same time they are also anti-science. I think this demonstrates a bias towards social issues over science (and often naivette or fear towards science) more than it indicates a yearning for things past or the other trappings of romanticism as described here.

The choice to dump the praise on a bunch of artists seems almost incidental in this case, even if the plot (as described, I've not read Atwood) seems fairly soap opera'ish and muddled in blaming hubris for what really comes out of stupidity and incomplete information. Such a story-telling framework could really allot blame and praise in just about any directions. Could not another postmodernist have dumped the praise on a more worthy (if still not scientific) group and not really violated any postmodernist principles (if there are such things -- it's not clear to me that there is any single set of rules for joining the postmodernist club).

I certainly don't like what is going on here and I've always had a bad taste in my mouth from postmodernists (even though I think that relativism itself is a useful platform for skepticism). When I think of postmodernists I usually think of the scene in Stephenson's Cryptonomicon with the protaganist's girlfriend's group of over-the-top liberals using absurd notions of technology to dismiss it as just another means of oppression, etc.

Such viewpoints, grounded as they are in such a poor understanding of science as it is, are certainly not harmless but I'm not sure they are romantic either. This literature does seem to perpetuate a fear of the unknown (or poorly understood or simply that which doesn't fall under one's specialty) which also seems a strong pillar of romanticism. And both Crichton and Atwood seem to want to burn science in efigee and dismiss it from the conversation because it might be inconvenient for their other goals. But is this really happening out of a feeling of romanticism or is it just a strong bias towards other types of solutions that prevents them from viewing and portraying science in an honest (or at least accurate) manner?

Thanks for reminding me that Glory Season was a complex thought experiment, not an exercise in polemic, which is what both utopias and dystopias are.

As for the postmodernists not being romantics, I beg to disagree.

Yes, some of their surface goals are progressive. So? My whole point has been to show that surface politics are being used to distract us from a real war that is going on at a deeper level of emotion and zeitgeist. When it comes to these surface issues, a pragmatic person - aiming to improve the world - might be tempted to pick among solutions that are being offered from any sincere source. "Two from column A and three from column B." Use BOTH adjusted market forces (that spur creative growth and revenues, including taxes) and social investment (in schools/education that stimulate meritocratic rise from all classes).

The point is that romantics of all stripes don't want that. They want to declare, ex cathedra, a PLAN for their vision of the world. And whether or not the plan is on the surface progressive, its psychological goal is victory for an elite clade of vanguard social leaders and their favorite incantation-dogmas.

These traits: *total demonization of opponents and exclusion of all their ideas, *authority for a chosen priestly class, *over-riding authority for a set of dogmatic incantations... these are all romantic traits.

As physicist Alan Sokal points out in his discussion of the Social Texts hoax, you don't have to give up all leftist-progressive goals in order to reject domineering left-postmodernists. Just as you don't have to reject classic conservative values in order to recognize that the new neocons are dangerous freaking loonies and enemies of the Enlightenment.

Oh, I agree with Sokal. Like I said, I think this is far from harmless stuff here and I would side along with Sokal to say: you guys are giving us Lefty's a bad name, stop it!

But I'm not ready to demonize the postmodernists in turn or exclude *all* of their ideas either. Wouldn't the postmodernist simply say that science is it's own brand of invocation-dogma and that it seeks to setup its own cadre of elitists? I think that is nearly exactly what they are trying to say, they are just getting it wrong (or taking otherwise not terrible ideas too far).

To say that I don't find many of the features of romanticism in postmodernism (I think they are just as suspicious of eternal verities and are forward-looking even if they have notions of what that means which are bizarre to us) is not to condone them. I think Sokal is careful to say that there are some good things that can come out of postmodernism (breeding skepticism of the role of money in science, for example) and I would follow that lead. Instead of demonization of the postmodernists (no matter how bad the taste they leave in our mouths) isn't a more nuanced discussion of their successes and failures possible?

gabe said, But I'm not ready to demonize the postmodernists in turn or exclude *all* of their ideas either.I don't think this was implied. We should acknowledge postmodernism's main contribution which can be encapsulated as "everything that is said is said by someone" but there's no need to embrace the postmodern agenda---which sees all of science as a power game and which seeks to blow up every text that it finds. Once the importance of perspective has been acknowledged, we can move on to figuring out how to integrate perspectives and not be caught in a relativist sliding nightmare of interpreting interpretations forever.

I agree what you are saying noone.

But I remain interested in whether postmodernism really fits on the romanticist side of the proposed dichotomy?

I have to wonder, for example, if they really are proposing a priestly class? If so then I think we need to have more evidence of this than one treatement in one work of fiction. If a modernist writes a book where skeptical, enlightened scientists save the day, I don't think it should be construed that they are proposing the creation of a society ruled by science elites. I think it rather more likely that postmodernists (as scientists) simply have a lot of faith in their own methodologies and think it likely that these methodologies will be the important ones that lead us to a better tomorrow.

That I think that postmodernists would level almost the same exact sorts of criticism at modernists that are being offered here -- that modernists hold onto an invocation-dogma and are seeking to create a priestly class of science elites -- indicates that there is actually quite a bit more common ground between modernism and postmodernism than is being allowed. The key difference, I think, is not really romanticism but just extreme skepticism (and IMO misunderstanding) of science. Postmodernists who take this skepticism of science too far (and/or use muddled reasoning to rail against science) are certainly antimodernists but that doesn't mean they must be romanticists.

All I have to say at this point, it that I consider myself an ultraliberal, and I have no interest in discrediting science. I'm taking classes about it right now and I'm having a hard enough time UNDERSTANDING it, much less discrediting it.

Jon

gabe said But I remain interested in whether postmodernism really fits on the romanticist side of the proposed dichotomy?As you said, perhaps seeing things in terms of dichotomies is problematic here. How about this category scheme?

1. Romantics, fundamentalists have trouble with evidence. See things in mythical terms.

2. Modernists have trouble with perspective and interpretation. See things in rational terms.

3. Deconstructive postmodernists have trouble integrating perspectives. See things relativistically and in terms of power relations.

We need to move toward a constructive postmodernism which integrates perspectives in a scientific framework.

One of the disputants on Contrary Brin said: " We should acknowledge postmodernism's main contribution which can be encapsulated as - 'Everything that is said is said by someone.' But there's no need to embrace the postmodern agenda - which sees all of science as a power game and which seeks to blow up every text that it finds. Once the importance of perspective has been acknowledged, we can move on to figuring out how to integrate perspectives and not be caught in a relativist sliding nightmare of interpreting interpretations forever."

I would go even farther in allowing relativism some value. For example, I believe I can fomulate a proposition that allows one to utilize moderate relativism beneficially, while preventing a slide into romantic incantory madness. Try on the following:

"Any person or class who proclaims that their subjective statements are superior to all others, or who claims to best-model objective truth, should face steep burdens of evidence and proof . All the more so if those statements serve to support self interest, or whatever the person or class most hopes to be true."

Notice that this proposition about a steep "burden of proof" is now perfectly compatible with science, which is comfortable with repeated challenges, tests and rigorous demands for evidence. It also opens the way for challenges to every ancient superstition and oppression based on mythologies of race or gender or other forms of artificially justified subjugation.

Oh, one can easily see the motives for postmodernist relativism. It started from a genuine opposition to modes of despotism and repression that had been justified by millennia of incantations and dogmatic statements by entrenched elites. The rationalizations of injustice had to be fought and for a while Romanticism and the Enlightenment worked on this great project hand-in-hand (Didn't I say they started out as allies, 250 years ago? )

Only the two movements diverged over how to fight injustice.

Modernists chose to demolish oppressive justifications by disproving them.

Romantics chose to fight the same rationalizations with counter incantations. With spells that use words and language to neutralize the doctrines of racists and sexists and capitalist elites.

Alas, that made them rationalizers, themselves, a path fraught with dangers, and lacking the self-correction mechanisms of science. For some, this process culminated in the horrors of Marxism, which pivoted full circle to become the Official Church of yet another oppressive ariostocracy. Leftist romantics spent three generations trying to come up with dialectical excuses for this calamity, before grudgingly admitting it had happened. Then they hurriedly sought other foes to distract from that embarrassment.

Which was when postmodernists decided that science itself must be one of the oppressive elites. Even though science had been spectacularly effective at undermining prejudice, using its own methods. (Perhaps this very success made it a loathed rival - magicians are like that.)

In any event, postmodernism soon classified science and modernism as enemies. But they could not be taken on at the level of evidenciary challenges. That is where science has home court advantage. (Romantics of the right, including Creationists, face the same problem.)

No, science and modernism had to be fought at the root semantic layer, by rejecting all recourse to evidence or objective reality, and using the verbal methodology of incantory magic.

=============

"The displacement of the idea that facts and evidence matter by the idea that everything boils down to subjective interests and perspectives is -- second only to American political campaigns -- the most prominent and pernicious manifestation of anti-intellectualism in our time."

-- Larry Laudan, Science and Relativism (1990)

"Everything that is said is said by someone." That's a tautology and the danger of tautology is not that it isn't true, but undue emphasis put on the fact.

So what if someone said it? It is

implied by the postmodern stance

that there may be agendas, biases

and prejudices. It is implied in this stance that the manner of the saying refutes the content.

This is of course hogwash. What

the postmodernist is assuming is

that humans are incapable of discerning justice, equality and objectivity. A judge in carrying out his duties is incapable of being professionial, and always let's his biases through. A scientist in donning is lab coat introduces systemic errors in his readings.

Of course, SOMETIMES they are right.

When they are right, there are known

ways to correct the error (rehear

the case, use a different experimental setup.) It is THEIR agenda, which is to undermine our general confidence in our capabilities to cope, that shows us what a postmodernist is.

This is why postmodernism is anti-modern and anti-science.

Anders said

""Everything that is said is said by someone." That's a tautology and the danger of tautology is not that it isn't true, but undue emphasis put on the fact."

It may not be true of sentences produced by a machine. Or, a machine perspective would have to be taken into account.

Dr. Brin said

"Any person or class who proclaims that their subjective statements are superior to all others, or who claims to best-model objective truth, should face steep burdens of evidence and proof . All the more so if those statements serve to support self interest, or whatever the person or class most hopes to be true."

Instead of "objective truth", wouldn't objective phenomena be better suited, or just phenomena? Also, "steep" is a bit vague. These are just nitpicks though.

I don't mean to be rude Dr. Brin, but I see you and yours as getting dangerously close to practicing the methods of your enemies. This running essay seems to be getting really close to demonizing all of your opponents, looking back fonding on the past (the enlightenment), describing a horrible downward slide through the ages (another romantic trait) and a huge exercise of "The indignation that feels good."

Not to mention that some of these posts against postmodernist are starting to read (to me anyway) as getting really close to postmodernism itself. I went to the website described above (the postmodernist generator) read a sample, then came back here and kept reading the antipostmodernists posts in this installment; I have to tell you, I couldn't see too much of a difference.

I hope that I'm wrong about this, but I'm starting to see this essay (and the current, "How could so many of my fellow citizens have been so stupid/brainwashed to vote for Bush?" rants, which I've engaged in myself) and the posts responding it as starting to take on the elements of "those few, cloistered, incantation elitists" that you constantly decry.

Maybe I'm no better, but I am trying to be.

Jon

Jon,

I don't understand your position that the "Enlightenment" was in the past, that we should get over it somehow. This is a not a viable stance. Modernity, as far as I can tell, means critically examining

the values, practices and lessons of the ages past, and holding the view that none of them are sacred, that one can analyze, synthesize and choose use these knowledge for the improvement of mankind. These are all enlightenment values. The only reason Dr Brin cites them is NOT to commit the sin of believing

that he is one sole originator of these ideas.

Critically examine the postmodern position's tenets, if you will. Is there anything in them that improves upon the human condition? Science is dethroned? Who then sits upon that throne? Truth is relative? So there is no such thing as economic truth?

How can any of these tenets make any sense?

There may be some things that the postmodern gets right. I don't doubt that. But their central tenets are untenable, and their stance is generally antimodern and antiscience.

I see myself as pragmatic, and strive to consider ideas rationally. Until reading this essay series, I was pretty much oblivious to the names of these different schools of thought.

Very interesting stuff. Being somewhat of an empiricist, I've been trying to match up my own experiences with the points in Dr. Brin's essay(s).

When my opponent in a debate chooses to appeal to the "subjective-ness" of a concept, that seems post-modernist to me now. (am I wrong?)

There have been some useful tidbits that would make a good "How to Identify a [Postmodernist | Romanticist ]" guide.

The issue I have with such a classification is that it could lead to stereotyping and dismissal of ideas a priori (which can, of course, be useful to persons with finite time). For example, "so-and-so used this phrase, which is a Postmodernist idea. Now I don't need to read the rest of his argument."

The Harvard/Summers hyper-PC business seems to be related to this essay... maybe the intoxicating effect of indignation and the liberal tendency for intolerance while preaching universal tolerance...

-Dave

Dave,

I don't think it is the ONLY the subjectiveness of a concept that identifies a postmodernist. It's the stance. You have to distinguish between an idea, and a stance.

One very interesting example I

would like to bring up is Bertrand Russell and his book "The ABC of Relativity". I read that years ago when I was trying to understand it. Now in his exposition, he was absolutely clear on the math, and he made only one confusion that a modern physics student would not make. However, when he leapt to the philosophical elucidations of relativity, he made one essential mistake, which I consider to be the precursor to the postmodernist's confusion of objectivity and subjectivity.

The mistake he made was in saying that relativity has reduced many physical statements to convention. "What we once thought as firmly physical truths are have not been reduced to conventional truths like there are three feet to a yard." (Please pardon my error in quoting, I am recalling from memory.)

This is wrong. It is true that in believing the physical theory of special relativity, you will have to regard many quantities as coordinate dependent. But there are still quantities that are preserved under the change of reference frame, and plenty of physics can be done there.

But a postmodernist will pick up on that statement and run with it as Russell did. Einstein himself never made that mistake. And Russell himself was never postmodern, (even though he does precede them by quite a bit.)

That I think is one of the problem with postmodernists. The refusal to deal with a reality that is part subjective and part objective. It is not true that the subjective will subsume the objective (as they are wont to say.)

I have to wonder how many commenters here, including Dr. Brin, have actually read anything by any postmodernists, instead of only reading things about postmodernists.

It is completely and factually incorrect to say that postmodernists yearn for "eternal verities", complain about "traditional values under threat", or claim that "the past knew better". Postmodern thought has always involved showing that "eternal verities" are historically contigent and has always been resistant to notions that claim to explain everything.

There is a popular response to hearing about postmodern critiques of science which goes something like, "oh, they think everything is relative, so the fact that the speed of light is 3 million kilometers per second is just a matter of opinion to them". This involves fallaciously assuming that "science" just means the physical sciences like physics or astronomy. "Science" also involves sciences that examine human beings, like organismic biology, psychology, anthropology, and economics, sciences where there is a lot more interpretation going on. It is these human sciences that are the ones used to justify social policies, and those doing the justifying are greatly aided by a view that says "science (of any sort) provides direct unmediated access to The Truth".

Yes, science has self-correction mechanisms. But people using science to justify social action don't have access to tomorrow's version - they have to use today's, and they have to say "well, I guess that was a tough break for you" to lobotomy patients or thalidomide babies when "the latest science" turns out to not have all the answers. And let's also mention the Tuskeegee syphillis experiment "participants" in someone's search for knowledge.

(I'll note that postmodern thinkers don't expect that everyone will take anything they say as unvarnished gospel truth - they lay into each other all the time. Derrida first got everyone's attention critiquing an article by Foucault, and my copy of Lyotard's The Postmodern Condition has an introduction by Frederic Jameson that points out both what is good and what is flawed about the rest of the book.)

"Science is dethroned? Who then sits upon that throne?" What a very monarchist metaphor for a discussion by believers in democracy! Why must any belief system necessarily "sit upon the throne" and be the court of final appeal for social decisions? Why not let there be a discussion, including non-science systems of thought that have proven pragmatically beneficial?

One ultimate message of the postmodern critique of science is "don't shut your brain down and automatically fall into line just because someone presents a questionable line of action as 'justified by today's latest science'".

-- Erich, B.S. Caltech, 1991 (look for my name in your copy of Earth)

I of course should've said that the speed of light was 300,000 kilometers per second in my previous comment. -Erich

Well said Erich and Jon. I find it interesting and encouraging that I agree more than I disagree with most of the posters here.

I am very interested in the phenomenom of culture shock. It has very practical relevance to me as my fiance is German and I have to deal with her feelings about my culture and my own about hers. Anyway, a while ago, I was walking through an art shop with my fiance and I happened upon a postcard that I thought had a very insightful quote on this. It said something like:

"When greeting another culture, try not to judge it only as a failure to recreate your own."

I fear that is what is being done here by judging postmodernism (and by association, relativism) only through its inability (or more likely lack of desire) to reinvent the scientific apparatus for theory building. But I think that is as it should be. Relativism relates to science as a meta-theory of sorts, something that lies outside the realm of the standard procedures of the scientific framework. As such, it is inappropriate to simply label it unscientific and dismiss it. That would be missing the point.

As for the charge that postmodernism is "incantory magic" I have to wonder that means. I am worried that this charge is becoming a sort of incantation of it's own: if it's not science, it's crap!

Science is principally a human enterprise fraught with the same human frailty of any other enterprise. For a scientist's treatment of this, Feynman's famous essy on Cargo Cult Science is an excellent read. It's a great essay but it really only scratches the surface. When judging the successes (and yes failures) of science it is appropriate that he who watches the watchers operates at a level above or below with framework suited for the purpose as they are critiquing this very framework.

Science and relativism are both simply tools. Tools which can used well or poorly. My concern with Atwood and some of the other objectionable instances of postmodernism is not that they work outside of the scientific framework and not that they are romantics (far from it IMO) but just that they can be very inconsistent and that they treat caricatures of science instead of the same thing.

In other words, it's not the framework or the methods of postmodernism that have problems but rather it is that these are often used quite poorly (just as science can be done poorly).

Erich said:

"I have to wonder how many commenters here, including Dr. Brin, have actually read anything by any postmodernists, instead of only reading things about postmodernists."Actually I must confess I really don't know that much. I have read a lot on cultural and moral relativism from the anthropological and philosophical. I am a big fan even though I think I fit in the modernist mold. Relativism seems an important component for dispelling the "eternal verities" that so many seem to cling to these days.

I guess I'm sort of a pragmatic nihilist. When pushed I think that we must confess that pretty much all we believe is based on that which is subjective and that any statement about objective reality is fundamentally a statement of faith. However I think that is just a starting point, and often a boring one, as it is easy for us to agree on certain assumptions about the world, those assumptions which we implicitly assert whenever we decide not to walk into traffic, jump off tall buildings, or posit that the sun will come up on the next morning. And so I think we take those assumptions, knowing them to be at best only theories about the world, and go from there. Those who disagree are invited to go jump off of a tall building of their choosing. :P

Gabe.

To Anonymous,

When I put quotes around "Science is dethroned", I meant that I got that from a postmodern text (Sandra Harding, I believe). This was from a text in the 1990s. This phrasing was employed by a postmodernist,

revealing their agenda.

I think most of us are forgetting that postmodernism is a form of radicalism towards nihilism. And like all forms of radicalism, what we should be asking is: what are these guys reacting to? The answer is: science and modernity.

Gabe said "When pushed I think that we must confess that pretty much all we believe is based on that which is subjective and that any statement about objective reality is fundamentally a statement of faith."

I must take issue with this. Just because we cannot be truly objective since we can't step out of the universe and watch it does not mean that we should swing to the other extreme and claim that every statement regarding reality is based on subjective belief and faith. While it is easy to hallucinate when you are alone, it is much harder for pairs or bigger groups to have the same hallucination. Intersubjective checking of facts and ideas is the cornerstone of science and is too easily forgotten when we lurch from the modernist extreme of objectivity to the postmodernist extreme of subjectivity. Or in other words, the second person perspective especially when oriented towards evidence can ground both the third and first person perspectives.

A small copy-editing note: Atwood's recent book is just Oryx and Crake, with no "the"s. --Erich

"I don't understand your position that the "Enlightenment" was in the past, that we should get over it somehow. This is a not a viable stance."

I'm used to thinking of the Enlightenment as a term for the beginning of the scientific revolution, Ben Franklin, Thoms Jefferson, Washington, etc.

It seemed to me that this ongoing essay has taken on the forms (science is dethroned, those were the good all days, it's all been downhill for so long, the anti-moderinsts are left, right everywhere etc. etc.) of a "Romantic" anti-present rant as described elsewhere on this site. I keep looking for terms that describe today. Post-modern doesn't work, Nor post-post modernm, futurist, near future (isn't the present always that?) science fiction dreams that didn't come true etc. etc.

By the way, I noticed your name as Anders. Any chance that you are Anders Sandberg? (I've checked the Mage-related posts on his website in the past, as much of his science stuff as I can understand (i.e. not a lot)

It'll be interseting to see what conclusions David Brin draws in this essay and where it ends up. Kiln People was about copying parts of yourself, sending them out to learn and report back (and more) and I wonder if the author feels as though he is in the novel when reading these posts. (which means that I have to log off before my time expir-

Hi,

I'm not Anders Sandberg.

Jon said:

I must take issue with this. Just because we cannot be truly objective since we can't step out of the universe and watch it does not mean that we should swing to the other extreme and claim that every statement regarding reality is based on subjective belief and faith.Let me be clear that this is not a position I take because I particularly like it. I take it because I don't feel that anything stronger is really justified. Any stance that I have ever encountered on objective reality always relies on a large number of assumptions, or faiths. It is a faith of sorts that, in the end, allows me to believe that the sun will come up in the morning or that the next moments of my existence will have any relation to the prior ones. It's a faith of sorts that lets me believe that the other people around me are real beings, as myself, and that we really share a common experience. To try and build up any other rationale for this simply strikes me as an impossible boot-strapping exercise.

As, however, I think that we already have the best epistemological basis possible for any situation (one never could receive evidence that would make them more certain of objective reality), I don't take it too seriously. That is, I take these faiths as elmentary and non-controversial and given that I don't think we can boot-strap ourselves to any greater confidence bout our place in the world, I don't dwell too long in epistemology. Even if we imagine a person who is truly hallucinating his entire experience, and is alone in his world, that person would try to determine which features of their hallucination were constant and would try to learn how best to get by in a hallucinatory world -- and that's what I'm doing. After a fashion I no longer care if I'm being deceived by malicious Gods or not, I just do the best with whatever reality I'm presented. I operate from this level not because I find it aesthetically pleasing to say that I operate from subjective assumptions, or because it fits my agenda to do so, but because I find that there really isn't a terribly good argument for anything more secure or "objective".

Gabe.

Gabe said:

"I don't take it too seriously. That is, I take these faiths as elmentary and non-controversial and given that I don't think we can boot-strap ourselves to any greater confidence bout our place in the world, I don't dwell too long in epistemology."

Yes, but we may have a fundamental disagreement here, since I deny this. For me, the second person (intersubjectivity) is more important than the first person and is the basis for building up a consensual and relatively stable model of reality. I didn't see you discuss this in your response.

For me, the second person (intersubjectivity) is more important than the first person and is the basis for building up a consensual and relatively stable model of reality.I responded to this, but indirectlyh only. The very notion that you are in facting sharing an experience with other people similar in nature to you is something you come to only after filtering your first-person, subjective experiences. One can't really prove a solipsist wrong, one can at best only understand their solipsism to be not terribly interesting or useful for the pragmatic process of going out and acting in the world.

I think that matching your experience with other people is valuable. But this is something that we arrive at only after taking, on a sort of faith, many principles about the world. The ability to compare and share our experiences is predicated on an assumption that there is actually a commonality or consistenty between these experiences -- something that has pragmatic value but that I don't think can be "proven" in any final or absolute sort of way.

To me, a treatment of these things as somehow a priori true is itself a sort of "eternal verity". I'd rather admit that the ground is shakier than that but then have the pragmatism not to get too mired down in this ultimately not very interesting conclusion.

Gabe, you said, "One can't really prove a solipsist wrong, one can at best only understand their solipsism to be not terribly interesting or useful for the pragmatic process of going out and acting in the world."

Let me give you an unconventional answer to why a solipsist must be wrong. Let us pretend that a solipsism is correct, that there is a single solipsist in the world, and the rest of us exist only in his imagination. What kind of mind would this solipsist have? Well, the solipsist's mind must be multiply schizoprenic, because in his world, he can find many people who disagree with him, and can go on extended arguments with himself against solipsism. His mind must be subtler than the subtlest mind, becuase even the subtlest mind must just be a part of his mind. This is absurd.

Either this mind is God, or he does not exist.

So, you can choose to believe in solipsism and God, or you can disbelieve and not be solipsist. Note that this DOES NOT prove that if you believe in God, you must believe solipism, rather, if you believe solipsism (even if you are not the solipsist), you must believe YOU (not just him) are God.

As you said, no argument is wrong. But I stop here and leave you to draw your own conclusions.

This is absurd.Why? It sounds complex and perhaps a bit non-intuitive but it doesn't sound impossible. Quantum mechanics (what I understand of it, I'm not a physicist) is also very complex and non-intuitive but I don't think it be a terribly good argument to say, "no, that's just too weird, it can't be."

Either this mind is God, or he does not exist.Well more than one religion is based on principles like this. :)

So much wonderful discussion among bright and erudite people! I am proud to be a stimulator of such minds. I certainly (!) respect those who came here to disagree.

Having said that, I feel some clarifications are in order before I do the next section.

1) about the matter of objective reality, please don't imagine that we are the first to face this quandary. In fact, the most common (and boring!) of all "wise" pronouncements... offered by Socrates, Plato, Buddha, Jesus, Confucius, Carlos Castaneda and ten thousand other sages has boiled down to -- "We cannot trust our fallible senses."

Now at first sight that sounds like the key to science, and indeed, it is a good 1st step. But it hasn't worked out that way, because for 6,000 years they never took the vital second step! In fact, nearly all of these great sages - and countless others - followed this great insight with a calamitous follow-up.

"We cannot trust our fallible senses.... therefore GIVE UP and seek truth elsewhere."

They differ only in petty details of how and where else to look INSTEAD of the real objective world.

Plato & Socrates say we should seek truth through incantations of so-called logic. Castaneda prefers incantations of mumbo-jumbo, cross-cultural mystery magic. Jesus says we should turn to incantations of faith. Buddha, incantations that withdraw the mind from the world... and so on.

Can't you see the pattern? Every "wise man" NOTICES that the senses can't perceive objective reality very well (true enough). But then he prescribes a path of ritualized, liturgical salvation that involves running as fast as possible away from the Real World.

I illustrate this in the following passage from The Transparent Society, in an imagined conversation between Plato - the greatest of all enemies of science - and Galileo, the first modern scientist, who finally offered another way.

---------------

Plato to Galileo -- “Our senses are defective, therefore we cannot discover truth through experience. That chair, for instance. Despite all your gritty ‘experiments’ you will never determine what it is. Not perfectly.

“Empiricism is useless. Therefore give up! Seek the essence of truth through pure reason.”

Galileo to Plato -- “You’re right. My eyesight is poor. My touch is flawed. I will never know with utter perfection what this chair is. “Nevertheless, I can carve away untruths and wrong theories. I can demolish fancy ‘essences’ and epicycles, and disprove self-hypnotizing incantations.

“With good experiments -- and the helpful criticism of my peers -- I can find out what the chair is not.”--------------

Let us be very clear about this. Science is a process by which models are created and destroyed. But every time one is tested, compared to experiment and cast down, a new and better approximation model springs up in its place. I have compared this to the imagery of the Dance of Shiva, the destroyer god, who - by destroying the world - automatically makes a new world appear. (See? I can use romantic imagery in the service of science!)

This is a very different thing from what postmodernists do. Their "relativism" is NOT scientific skepticism. It is something far older. It is denial of the useful validity of objective reality, in favor of a prescription for faith in the power of word-based incantations! Exactly the ancient pattern.

And don't forget there most definitely have been many postmodernists who have stated, baldly, that objective reality does not "exist." Yes, today, this extreme stance has been forsaken by most (retreating from howls of derision).

And yet, the basic stance remains the same. Objective reality may exist, but turning to it will only prove futile. Our models are illusory or unusable or defective because of human subjective fallibility.

Oh, they are Platonists, through and through. Just like their supposed enemies, the neocons. The things that separate them, like a "left vs. right" political axis, are important in certain way. But not as much as starting to realize how much they have in common.

2) One of you made a good point:

"It is completely and factually incorrect to say that postmodernists yearn for "eternal verities", complain about "traditional values under threat", or claim that "the past knew better". Postmodern thought has always involved showing that "eternal verities" are historically contingent and has always been resistant to notions that claim to explain everything. "I can see where this person came up with this. (Although I doubt the quotation marks actually give exact citations of phrasings that I used.) Certainly he seems to have found a way in which the PMs don't follow a classic romantic pattern. I pondered this a while...

...then realized that it's simply untrue. Their eternal verity is scholasticism. Defense of the declarative power of an incantory elite whos eposition has been usurped by tradesmen, mechanics, craftsmen and such, not hyper-elevated by science. It is true that today's scholastic elite is profoundly cynical! Their alternative to science does not offer transcendence or salvation. No wonder, since these fellows are heirs of Sartre and Camus.

But then, despair is one more way of saying "give up." It is religious in its own way. (Frankly though, I find the fizzy, Alcibiades-hubris-arrogance of the neocons far more attractive, since if they DO prove to be right, some good may come. If the cynics prove right, we're doomed.)

Yes, the lefty PMs have a surface political agenda of 'liberation'... but always in theory.

Another contributor said:

"When greeting another culture, try not to judge it only as a failure to recreate your own."Another great point and utterly delicious!

Only one culture in all of history has promulgated "otherness" as a central virtue. (See my famous essay about otherness, found in my collection entitled... well... OTHERNESS.) The reasons for this new way of looking at the world are ironic. Only a people filled with confidence in their own safety and satiated desires could begin to look upon the alien as inherently attractive BECAUSE it is alien. Name for me another culture that promoted this weird idea to anywhere near the extent that modern Western Civ has... while portraying itself as the great criminal transgressor AGAINST this value.

Now mind you, I approve deeply of otherness. I am a prime practitioner. I am a science fiction author and futurist. I like our expanding horizons of inclusion. I have benefitted from this expansion, immensely, and foresee a better world filled with empowered diversity.

But science did this. Modernism did it, vastly more than the antimodernists ever dreamed of.

Moreover, they never perceive the irony! When they shout and denounce and hold forth about the imperatives of hyper tolerance, they are beating the drum of THEIR cultural value system! No other culture believed such things! That eccentricity, diversity and difference-from-the-norm are paramount attractive traits? Can they really promote this without a scintilla of awareness how outrageously CHAUVINISTIC they are being?

The contributor who said: "When greeting another culture, try not to judge it only as a failure to recreate your own." should not try to teach his grandmother to suck eggs. I practice this every day.

And yet, I am not being intolerant of another culture when I criticize inconsistencies and things that I find bloody dangerous in a self-styled hyper-elite. Postmodernism is a dangerously nasty, reactionary movement, aimed at undermining the one cultural trend that ever offered hope to humanity for better days. A world made better with goodwill and our own skilled hands. Postmodernism deserves some of the "criticism" that it heaps (spews) in all directions to come back at it.

Finally, someone said: "As for the charge that postmodernism is "incantory magic" I have to wonder that means. I am worried that this charge is becoming a sort of incantation of it's own: if it's not science, it's crap!"Remember who you are talking to. I may be trained as a scientist but I was born an artist. A musician, a poet, the child of many generations of known poets. I make a living at being a romantic! And I do it by performing incantory magic of the most powerful and effective form - the creation of people and worlds and then the spectacular conveyance of those worlds INTO THE MINDS OF OTHERS, through the use of words alone.

It is the greatest and most powerful form of magic and I am an adept of the first order. So don't tell me I don't know incantory magic when I see it. Even science has plenty of this human creative art pouring through it daily... though in the long run, its most noble trait is that there always comes a noonday sun of experiment, under which the dream images and persuasive words melt away, leaving Truth.

Truth... about which yet MORE sugarplum metaphors will then dance till the next noonday sun.

That is wht I like about science. It doesn't banish art and romance and magic. But it does make them sit down and shut up and do their homework once a day, before going back outside to play. None of the other magical systems ever did that. Certianly the postmodernists don't.

I tell you this. These magicians are very good. Like politicians and lawyers and other spell-weavers. They spin out words and create subjective images. We are human and that's what our brightest do.

But I am grateful above all to a civilization that TESTS the spells. That process of Galileo's finally led to the Enlightenment that we live in today (just barely, still). It is the reason that 6,000 years of hellish domination by nobles and aristos and warriors and priests and magicians may give way to something far, far better.

Gabe,

I wasn't clear enough. It's complicated yes, but the point is that it is also logically absurd. For a solipsist, what is the answer to the question: How many people are there in the room? The solipsist will look and say three, but then remind himself, "But I am a solipsist, so they are illusory, hence there is only one." If THREE == ONE, then we are in big trouble.

Of course, I am indulging in a bit of what Dr Brin calls "incantatory magic". Guilty as charged!

Dr Brin,

Thank you for putting the finger on PM as a form of scholasticism. For categorizing Confucius along with Plato and others, I think you may be on to something.

Confucius is interesting because he anchored Chinese civilization in scholasticism. He wasn't antimodern, and and he wasn't antiscience (There wasn't any science around for him to affirm or deny!) He did develop a school of thought that sought to employ the rites of religions to perpetuate a political system. In this he was wildly successful and his contributions cannot be denied. But where it did not work was precisely that he did not encourage empiricism. Thus, after maintaining thousands of years of relative peace within the borders of China, did it spectacularly fail under the guns of Western Civilization.

The point is that scholasticism does have it's place. Don't underrate it as a pillar of civilization! So maybe the postmodernists do have a place - just not in discovering truth or dictating policy.

Dr. Brin said

"Buddha, incantations that withdraw the mind from the world..."

Sorry, but this is simply false. Buddha was an empiricist regarding experience and far from withdrawing the mind from the world, he gave instructions on how to use the mind to investigate the senses themselves. This is what meditation does - it allows us to investigate the content of our senses. The senses are also IN the world, so when you investigate experience, you are investigating an aspect of nature.

Dr. Brin quotes me:

---

"It is completely and factually incorrect to say that postmodernists yearn for "eternal verities", complain about "traditional values under threat", or claim that "the past knew better". Postmodern thought has always involved showing that "eternal verities" are historically contingent and has always been resistant to notions that claim to explain everything. I can see where this person came up with this. (Although I doubt the quotation marks actually give exact citations of phrasings that I used.)

---

I now present in full the exact paragraph from which my quotes are taken (emphasis Dr. Brin's):

---

Dig down, and you will find that these authors, and a myriad others like them, tap the mythic current described by Joseph Campbell. A river of tradition, nostalgia and fear of the future that watered nearly all of the great literature in our tortured past, from Homer and Murusaki to Joyce. A despairing sense of loss. A belief in eternal verities and traditional values under threat. The rightful superiority of a wise or all-knowing class. A sense that the past knew better and that today's citizens cannot be trusted with bold new tools to "improve" the world. To improve their children and themselves.

---

Dr. Brin's claims that postmodernists support the eternal verity of "scholasticism": "[d]efense of the declarative power of an incantory elite whose position has been usurped by tradesmen, mechanics, craftsmen and such, not hyper-elevated by science". I wonder what he would make of the fact that many postmodern critics of science actually hold degrees in the sciences themselves, i.e. they know what they're talking about and are not doing what they do out of spite or "sour grapes". For example, Donna Haraway, with a doctorate in biology, or Katherine Hayles, with an advanced degree in chemistry. (I especially recommend Haraway.)

Postmodern critics of science do not reject the useful things it has wrought. They reject its use by elites as justification for exerting power over subordinates, those actions done in its name which are coercive and unethical, and certain attitudes about science that aid and abet the aforementioned.

--Erich

Having read Foucault, Derrida, etc. I think it's unfair to even group them together. There's some big differences between them. The areas of interest are different, for one thing. Foucault strikes me as a social historian, Derrida seems concerned with language, and I've never been able to figure out what Baudrillard is going on about.

Unless you're just grouping them together on some basis of essential Frenchness, I'd recommend separating the original thinkers from the so-called "postmodernist movement".

Most of what I see go down as "postmodernism" is just rehashings of vacuous Baudrillard junk and has very little to do with the core content of Foucault, Baudrillard, Althusser etc.

"Confucius ... But where it did not work was precisely that he did not encourage empiricism."

I thought that the Confucian system said that a ruler should show how well they would rule in one small province before being trusted with the entire nation.

I should admit something here; thought I am not a Communist (because I hate authority/totalitarianism) or a magician (I hate superstition) there was something I found tempting about both of them: I always believed in something like the need to do better than my ancetstor, leave the world better than I found it (pretty much the modernist view David Brin describes) and I reasoned, "I was born into a capitalist system, therefore I must tear it down and replace it with something better; I was raised in a world of science, therefore I must find the flaws in it, and replace it with something better."

Okay, it's simplistic, it's late, I'm tired.

Lastly, I have to ask David Brin: how do you police yourself againt the problems of hubris ("I'm an adept of the first order...etc.") and the high of indignation (how DARE they!) I know that you believe that Cricitcism Is The Only Known Antidote To Error, but isn't that a little simplistic? What about self-testing, taking a second look, etc...?

Jon

Jon, thanks for your question.

Indeed, I believe that individual human beings have an obligation to learn many techniques for improving their accurate extrapolation of the likely consequences of their actions. This effort CAN result in greater morality. But it is also aimed at pragmatic self-interest. It is startling how often these two things can be the same thing, providing society is set up in order to make it so.

(This is why a "regulated" market is the only market that ever worked. In order to compete with each other fairly, we muct first be encouraged not to cheat.)

There are many stages in this honest self-evaluation. Imagination lets you picture a wide range of possibilities. Culling lets you throw away the 99% that are obviously foolish. Analytical methods let modern people throw out another nine tenths, as in business plans etc.

I could go on and on about that. But in the end, we have to recognize that the one greatest human talent in lying. (I am one of the best - I'll gladly brag. I am well-paid to spid tales about people who never were.) It is the one great and true magic.

And as Feynmen said, the easiest person to fool is yourself.

No, in the long run, we need an open society so that others can do us the FAVOR of criticism... a favor we always seem happy to return. ;-)

db

"(This is why a "regulated" market is the only market that ever worked. In order to compete with each other fairly, we muct first be encouraged not to cheat.)"

1)I'm not sure why you put regulated in quotes.

2)What I find a bit (odd? troublesome? interesting?) is that without the "cheaters" we'd be missing a lot of innovations. How many industries fought new developments that benefitted them in the end? Movie feared and tried to block TV, then they made more money selling to TV. TV and movies feared cheap VCR tapes and piracy, then they realized that they could make most of their money through tapes. DVD's the "easy transfer" issue (they'lll never pay us again ! argument.) which led to renewed interest (DVD extras.) When sellers tried to dictate or control the market, the pirates and consumers used new technologies to do an end run around them untill the companies charged a reasonable price and made more money than error.

They keep doing it, I remember the panic that came with the early mp3 players ("It's the end of music!") and the same fears of VCR's, DVD's and Tivo's ("They block/skip ads! We're doomed!) and I remember some products starting out as a non-licensed product (such as a shirt with the character) which led the creator of the character to say, "Hey, I didn't know that people would buy a product like that!"

Short version, the relationship between honest consumers, producers (honest, corrupt, greedy, nice, etc.) distributors and "cheaters" is more than I can figure out at this time.

Post a Comment